Click the image to enlarge

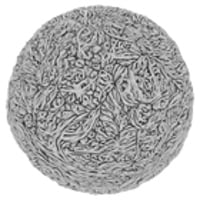

Click the image to enlargeCredit: Andy Lomas, Cellular Form 14_0017_0011, 2014.

Copyright the artist. Reproduced with permission.

Andy Lomas is a self-confessed code junky, saying, ‘I write it for my own pleasure.’ His Morphogenetic Creations on view earlier this year at the Los Angeles Center for Digital Art, has just been awarded one of the best artworks at the Artificial Intelligence and the Simulation of Behaviour (AISB) conference recently held in London and Cellular Forms was short-listed for the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition.

This summer his work is on view in A Glimpse of a Great Vision: The D'Arcy Thompson Art Fund Collection at University of Dundee.

As previously discussed in this column, Dundee Museums have spent the last two years building a collection of contemporary art inspired by the work of Sir D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1860-1948), their first Professor of Biology, with funding from the Art Fund. Daniel Brown, one of the commissioned artists was featured in 2013.

Thompson, an extraordinarily creative scientist and thinker, straddled multiple centres of knowledge and among other things, laid the foundations for the science of biomathematics. His famous book 'On Growth and Form', from 1917, was a study of how mathematical constraints and the physics of growth govern the shapes of living forms.

It has inspired many modern artists from Richard Hamilton in the 1950s. Mathematics and issues of form are of course of particular interest to computer artists who write and manipulate code, so much so that Dundee Museums is fast becoming a prominent benefactor of contemporary digital art.

In keeping with this select ‘Growth and Form’ artistic tradition, Andy is interested in how relatively simple sets of rules, his own mathematical algorithms, can generate extremely complex structures.

A Cambridge mathematics graduate, this British artist spent several years working in the United States at DreamWorks and ESC Entertainment, supervising computerised special effects for Avatar and The Matrix sequels (remember the dramatic rain effects in the closing scenes with Agent Smith?) among other famous films, winning Emmy awards for his work. In fact Andy is a successful example of a digital artist who happily combines both commercial and personal work, allowing each to feed off and inspire the other.

The natural world has always fascinated Andy, a keen scuba-diver especially interested in coral formations, something that Thompson also featured in his book. Andy’s series, Cellular Forms - of which our image this month is just one example, uses a simulated model of cellular growth to create intricate sculptural shape.

Structures are created out of interconnected cells, with rules for the forces between cells, as well as rules for how cells accumulate internal nutrients. When the nutrient level in a cell exceeds a given threshold the cell splits into two, with both the parent and daughter cells reconnecting to their immediate neighbours. Many different complex organic structures are seen to arise from subtle variations on these rules, creating forms with strong reminiscences of plants, corals, internal organs and micro-organisms.

Coding in C++ and CUDA for simulation and rendering, Andy says, ‘The aim is to create structures emergently: exploring generic similarities between many different forms in nature rather than recreating any particular organism, in the process exploring universal archetypal forms that can come from growth processes rather than top-down externally engineered design.’ (Videos of animated versions)

Our image this month is typical of the incredible detail in this series. When he prints images (as a 44 x 44 inch print), they are at an outstandingly high-resolution 12,000 x 12,000 pixels. To appreciate this fabulous degree of detail, it is well worth clicking on the image here. We have the impression that we could go on zooming into the image almost forever, as if down to the nanolevel. The original render of this work is actually at 8,600 by 8,600 pixels, our (expanded) image shown here is approximately half of that.

Andy tells me ‘I particularly like the animal / reptile skin nature of it, and thinks it’s good at illustrating the sort of emergent complexity that is coming from the simulation processes. There’s nothing in the simulation that directly controls such large scale fold and their shapes. Everything is a directly emergent up from the individual cellular level.’

Andy explains his current challenges, ‘The other less talked about half of the story is that the simulation engines for Cellular Forms typically have 20 to 30 parameters, which makes the task of exploring the space of possibilities to try to find the areas of interest quite a challenge.’

To assist with this he’s been writing additional software he calls ‘Species Explorer’, to help aid the exploration process: ‘Because this is mostly focused on interface rather than performance this is implemented in Python and PySide.

There’s probably too much to go into here about that, but one of the main ideas I’ve been working on is that the most interesting results from simulation engines like this tend to happen in “transition zones” between large areas of the parameter space that produce less interesting / more homogeneous results. Finding those transition zones where rich, and hopefully aesthetically interesting, results are produced is the challenge.’

They certainly are aesthetically interesting and like all great art, digital or otherwise, transcend the method and materials used to create it. We wish him all the best in his continuing coding conundrums.

Catherine Mason is the author of A Computer in the Art Room: the origins of British computer arts 1950-80, published in 2008.

More information on the Computer Arts Society, including our events programme